I’ve become a bit fixated on this idea of disgust and abjection. So, disgust can be understood as having the function of defining one’s limits; i.e., to say ‘that’s disgusting’ is to say ‘I wish to distance myself from identification with that thing’. That’s one understanding of disgust, anyway. Well, I know disgust. It’s one of the most fundamental ways in which I relate to my own sexuality. The origin of my sexuality – and I mean this in terms of experience of arousal, universal rather than specific to being gay – is disgust. I looked at men, I was aroused, and I was disgusted. I don’t know if it was quite as linear as that, the causality implies some kind of straightforward way in which I comprehended it at the time, but I think more accurately I was unable to differentiate the two sensations. Arousal was disgust; they were coterminous. And I don’t think I can overstate the significance of that. So long as I can remember I’ve been disgusted by myself. And obviously I’ve since ‘got over’ that (if such a thing can ever simply be ‘gotten over’) – I know that what turns me on is beautiful and not disgusting. Beauty’s where you find it. But I think these associations remain. I’ve normalised disgust. I think a lot of the rhetoric of pride in the gay community can have a somewhat blanching effect; we shout that we are proud of who we are but fail to attend to the shame that is a fundamental aspect of being queer. I can wear a rainbow and hold a man’s hand in public, but that doesn’t resolve that much of my identity was built around. Obviously I don’t want to paint the queer community as defined by shame and suffering, but I think this overemphasis on pride fails to attend to the shame that I think most of us have been defined by. I’m taking a class on disability/illness studies and one thread is that people generally struggle to deal with pain and so it remains largely ignored and unrepresented, and I think the same applies here: the glittery, happy version of the queer experience sits more comfortably, and so that’s the only narrative that is allowed to exist. And then I think people start to feel ashamed of their shame. At a pride parade it’s pretty shit to feel like you’re not fully comfortable with your sexuality. And, honestly, I think the truth is that I’m not fully comfortable with my sexuality. I’m proud of being a gay man, but I also harbour a lot of murky, shameful feelings around a sexuality that never felt fully comfortable. I would like to think that a lot of gay men / queer people in general feel similarly, but I don’t know because there’s not much space for that. I think queer people feel pressured to have a happy ending when they tell their stories; because queer stories have historically ended with tragedy we are held to higher standards than our non-queer counterparts. And I think this compulsory optimism makes us ill-equipped to deal with shame, a shame that can’t be uttered for fear of it manifesting itself, as though to discuss it is to perpetuate it. I’m not a psychologist, but I’m pretty sure ignoring shame doesn’t make it go away. I consider myself quite secure in my sexuality, but I have no fucking clue how to make this shame go away. I don’t know if such a formative experience can go away. It’s all a bit of a blur now – over the past few weeks I’ve been kind of working through my memory to tease out what I can only assume I’ve blocked out – but all of my formative sexual memories are drenched in this absolute disgust. Every time I had a wank I felt like I was letting myself down. To go back to where I started, I think it had this weird impossible distancing effect; my disgust was an attempt to dissociate myself from same-sex attraction, an attraction that I felt incredibly strongly. What kind effect must that have on a person? You just have to get on with it, get through,and I did. But I’ve ignored it for a long time, and now I’ve rediscovered it from the dregs of my subconscious it kind of makes sense; it certainly informs much of my action. ‘Is there no escaping the junk shop of the self?’ I don’t think there really is. I can’t pretend that I learnt about my sexuality in the same way as everyone else. For a long time I think I wanted to prove that I was just like everyone, with the minor qualification of being gay. But I’ve learnt that being gay can never be a minor qualification, no matter how much I wanted it to be. How I move through the world is massively informed by the fact that I’m gay. That means something different for every gay person, but for me I think it means that from a young age I had to navigate a lot of shame: shame for being attracted to men, shame for being friends with girls, shame for not doing all the things boys are meant to do. And I navigated shame poorly for a long time. I remember being twelve at school when a girl in class asked me if my mum knew that I was gay, and I burst out crying. Not because she’d found out my secret – I wasn’t anything at that point, I don’t think I’d felt any sexual attraction. I was viscerally ashamed of being associated with homosexuality before I even knew that I was gay. Shame preceded the sexuality. I remember telling a childhood friend when I was maybe eight or nine that my best friend was called Hannah and she was incredulous that me, a boy, might be friends with a girl. Lesson: being friends with girls is shameful. The more I look back, the more I realise that shame was never exclusive to me sexuality; it was more widely attached to anything that marked me as different. I was a little gay boy – everything marked me as different. I do wonder why I turned my difference into shame. I guess I wanted to fit in, and shame was a pretty effective means of quelling my difference, at least in the short term. To this day I’m fighting a constant battle with shame, one that I rarely win. But I don’t think pride and shame are mutually exclusive. I think I can say with confidence that I’m absolutely proud of everything about myself and that I’m ashamed of everything about myself. Maybe alongside pride we should have a shame parade – and that need not be as depressing as it sounds. It can be liberating to state your own shame, rather than having shame pushed onto you by others – this is the shame that pride is a protest against. Maybe there are some perfect gays out there who have never been ashamed of themselves, but then again maybe pride isn’t really for them; at the end of the day pride is meant to be the antidote to shame. Maybe this pride we can all take a moment to utter shame to someone – not public, maybe to a loved one or a friend or even a stranger, who cares. As long as we can be proud while attending to shame I think it can be productive.

Being happy

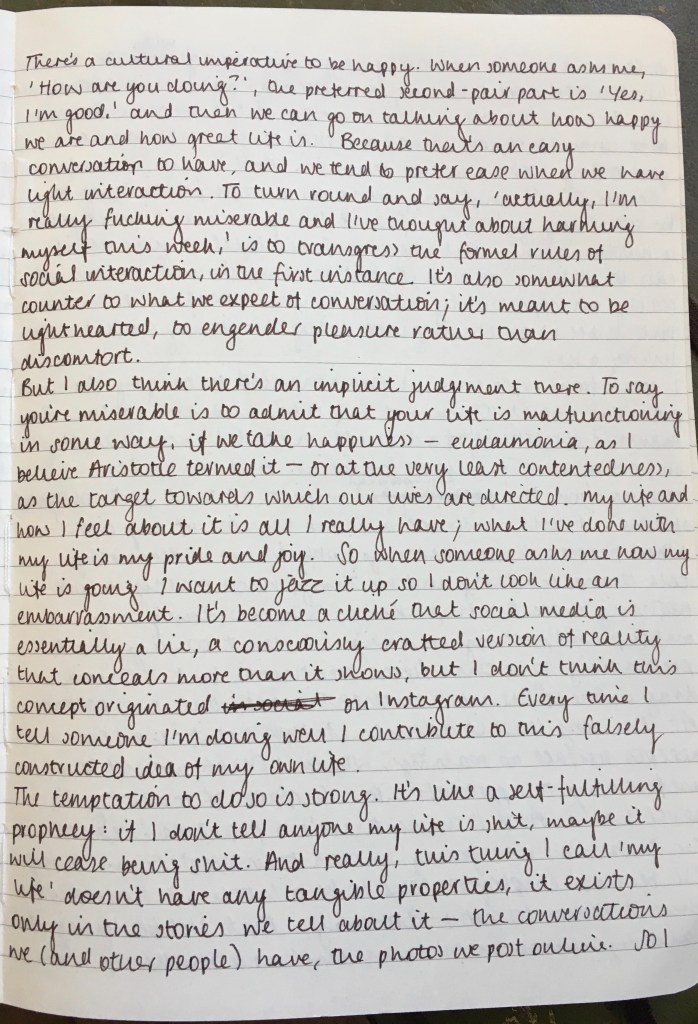

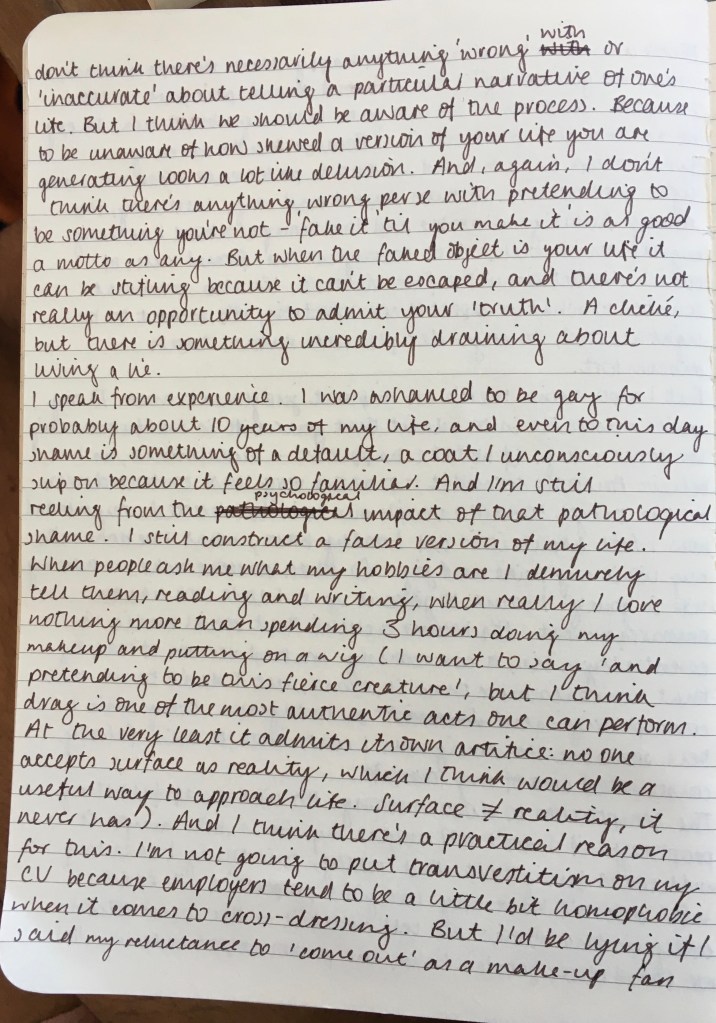

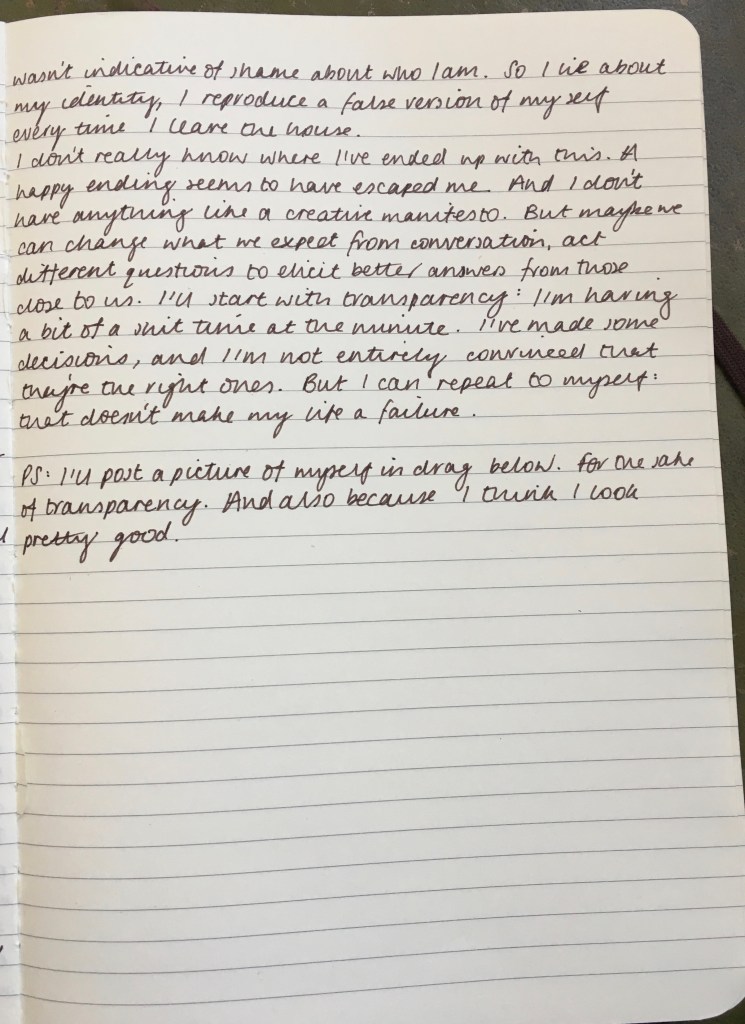

I’m trying something a bit new here. If I’m honest, I don’t really like writing things straight onto the computer; something about the computer keys don’t feel authentic. (Ironic that I’m writing these words straight onto the keyboard.) Might be a weird thing to say, but I’ve always felt much more at home with the pen in hand when it comes to writing, and I think my writing is a lot better. Using the pen feels like a better expression of myself because that’s the medium I’ve become accustomed to. But I also don’t want to edit what I hand-write in uploading it here, because the whole point of this is that I want it to be less thought-out. So I’m going to try something out. Below I’ve written something similar to what I’ve written before, but I’ve uploaded it as an image of the pages of my journal. I find it a bit more satisfying to write on paper and it’s also a slower process, which means I’m a bit more to the point I think.

Below I’ve also included a transcribed version, in case you can’t read my writing and to make it more accessible. I’ve also corrected any glaring mistakes (such as using the wrong word) which can happen when I hand-write things without checking, but I’ll keep that to a minimum because it feels a bit counterintuitive to what I’m doing.

Anyway, I hope this new format works. I’ll probably find it easier to keep on top of as well since I prefer hand-writing things.

[Transcribed:

There’s a cultural imperative to be happy. When someone asks me, ‘How are you doing?’ the preferred second-pair part is ‘Yes, I’m good,’ and then we can go on talking about how happy we are and how great life is. Because that’s an easy conversation to have, and we tend to prefer ease when we have light interaction. To turn round and say, ‘actually, I’m really fucking miserable and I’ve thought about harming myself this week,’ is to transgress the formal rules of social interaction, in the first instance. It’s also somewhat counter to what we expect of conversation; it’s meant to be lighthearted, to engender pleasure rather than discomfort.

But I also think there’s an implicit judgement there. To say you’re miserable is to admit that your life is malfunctioning in some way, if we take happiness – eudaimonia, as I believe Aristotle termed it – or at the very least contentedness, as the target towards which our lives are directed. My life and how I feel about it is all I rally have; what I’ve done with my life is my pride and joy. So when someone asks me how my life is going I want to jazz it up so I don’t look like an embarrassment. It’s become a cliché that social media is essentially a lie, a consciously crafted version of reality that conceals more than it shows, but I don’t think this concept originated on Instagram. Every time I tell someone I’m doing well I contribute to this falsely constructed idea of my own life.

The temptation to do so is strong. It’s like a self-fulfilling prophecy: if I don’t tell anyone my life is shit, maybe it will cease being shit. And really, this thing I call ‘my life’ doesn’t have any tangible properties, it exists only in the stories we tell about it – the conversations we (and other people) have, the photos we post online. So I don’t think there’s necessarily anything ‘wrong’ with or ‘inaccurate’ about telling a particular narrative of one’s life. But I think we should be aware of the process. Because to be unaware of how skewed a version of your life you are generating looks a lot like delusion. And, again, I don’t think there’s anything wrong per se with pretending to be something you’re not – ‘fake it ’til you make it’ is as good a motto as any. But when the faked object is your life it can be stifling because it can’t be escaped, and there’s not really an opportunity to admit your ‘truth’. A cliché, but there is something incredibly draining about living a lie.

I speak from experience. I was ashamed to be gay for probably about 10 years of my life, and even to this day shame is something of a default, a coat I unconsciously slip on because it feels so familiar. And I’m still reeling from the psychological impact of that pathological shame. I still construct a false version of my life. When people ask me what my hobbies are I demurely tell them, reading and writing, when really I love nothing more than spending 3 hours doing my makeup and putting on a wig (I want to say ‘and pretending to be this fierce creature’, but I think drag is one of the most authentic acts one can perform. At the very least it admits its own artifice: no one accepts surface as reality, which I think would be a useful way to approach life. Surface ≠ reality, it never has). And I think there’s a practical reason for this. I’m not going to put transvestitism on my CV because employers tend to be a little homophobic when it comes to cross-dressing. But I’d be lying if I said my reluctance to ‘come out’ as a make-up fan wasn’t indicative of shame about who I am. So I lie about my identity, I reproduce a false version of myself every time I leave the house.

I don’t really know where I’ve ended up with this. A happy ending seems to have escaped me. And I don’t have anything like a creative manifesto. But maybe we can change wha we expect from conversation, act [ask] different questions to elicit better answers from those close to us. I’ll start with transparency: I’m having a bit of a shit time at the minute. I’ve made some decisions, and I’m not entirely convinced that they’re the rights ones. But I can repeat to myself: that doesn’t make my life a failure.

PS: I’ll post a picture of myself in drag below. For the sake of transparency. And also because I think I look pretty good.]

Here’s the picture, as promised (it’d be cruel if keyboard-WRB didn’t honour the audacity of pen-WRB):

WRB

Stereotypes

When it comes to gender, stereotypes are pretty much unavoidable. In a sense, all that gender consists of is a series of stereotypes that are made to seem real by being repeated time and time again; gender exists as an ideal based around stereotypes which has no exact replica in reality. That’s how I understand gender to operate, at any rate. So, while gender depends upon stereotypes, there’s a general understanding that stereotypes are a negative thing, and I agree with this. No one really wants to be a ‘stereotypical’ man or woman because that position can be stifling or contradictory. I’m quite interested in this idea of stereotypes as a necessary evil of gender theory.

One way that I often see gender stereotypes deployed is to discredit trans people. The argument goes that trans men and women, in transitioning towards an ‘ideal’ of gender by taking hormones and having surgeries, reinforce harmful gender stereotypes. This could to some extent be true. A trans woman having facial feminisation surgery understands that there is a beauty standard for women and in conforming to this reinforces the stereotype which can then be used to marginalise those who do not meet it. But I don’t think it’s fair to aim this attack directly at trans folks. Cis women who wear makeup and dresses are reinforcing the same stereotypes, and so this attack could be applied to anyone who meets any aspect of a gender stereotype. It doesn’t make sense to demonise one marginalised group for doing something and let the dominant group get off without rebuke; that sounds like transphobia, to me. I appreciate that it’s more extreme in the case of trans women, but not that much more. Loads of women get botox, fillers, implants, to get themselves closer to their ideal of feminine beauty. And although I use women in this example, men are not exempt; they go to the gym to appear more masculine, grow facial hair etc. The point is that I don’t think anyone should be punished for striving to meet stereotypes that are ingrained within the fabric of society. It’s how and why they are met which can be praised or criticised.

There’s nothing wrong with stereotypes, per se. It’s how they function that ought to be critiqued. If a stereotype is applied loosely, as more of a framework, then that’s fine in my opinion. But when they are rigid and exclusive they can be damaging. I am critical of gender in a lot of ways, but I still have an understanding of what ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ qualities are, even as I understand them to be imaginary terms. In my head I have a loose idea of what a man is. But because I identify predominantly as a man doesn’t mean I force myself into this framework. At one time I tried to do that, when I was younger and less sure of myself. But I quickly learned that it wasn’t for me. And so I take these qualities of masculinity and apply them to myself when they feel natural: I like having a beard, for example, and I like being independent, a quality most often associated with men (and I don’t mean to say that women don’t possess this quality because I know loads of women that do, but in a traditional, problematic understanding of gender (which might be the only one we universally have), independence tends to signify masculinity). I don’t like football and I’ve never been a stern or confrontational person, and so I let go of those qualities.

That’s why I’ve never understood why criticisms of non-binary gender identities claim that they seek to eradicate gender. I guess it depends on the type of NB identity being referred to. Agender folks might seek to eradicate gender as they don’t identify with it (although I don’t think it’s true that identifying in one way makes you want to eradicate any alternative. Identifying as a man doesn’t mean you want to eradicate women). But my gender identity is aligned more with gender fluidity; I feel gender strongly, from both masculine and feminine ends of the spectrum. If I identify variously with both masculinity and femininity, why would I want to get rid of gender? I can’t follow that reasoning. My mental well-being depends on the existence of extremes of gender. I need those stereotypes to understand myself.

I think what it comes down to is a misunderstanding. I would like to relax notions of gender in the future, but I don’t want to get rid of gender. I don’t want to stop males from being men; I want to allow males to choose not to be men, if they so choose. Nowhere does that involve preventing males from choosing to be men (I find that it tends to be men who most strongly fear that NB identities will threaten their own gender identity). I want everyone to find the gender identity that suits them best. But it seems that gender as we use it – with its dependence on strict stereotypes – is a failing system. Traditional heterosexual, cisgender stereotypes are harmful to many individuals, myself included. But seeing gender as constructed, as non-essential, doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist. Lots of things are constructed, but it doesn’t mean they don’t have material reality. But what I think it does mean is that if gender is constructed and it isn’t fulfilling our needs as human beings – which I think it straightforwardly isn’t – we should be able to reconstruct it so that it functions better. I don’t think there’s anything particularly radical in wanting to change something that doesn’t functions as best as it could. Ideally gender would cease to exist, but I can’t see that happening, in my lifetime at least. But I think a movement towards relaxing gender stereotypes would be a step in the right direction, and I think it starts with allowing for the coexistence of binary and non-binary gender identities.

WRB

On Labels

I’ve noticed a whole lot of discourse lately about the labels we use to describe, especially ones in terms of sexuality. A lot of people who don’t really understand how labels work use language such as, ‘that makes me gay,’ or whatever, and I think language like this fundamentally misunderstands how these labels work.

Why do we use labels? Well, I think there are two main reasons for this. We pick a label so that we can more easily understands ourselves, and so that others can more easily understand us. So, I label myself as ‘gay man’ because when I was coming to understand my sexuality there was a pre-existing category of ‘gay man’ that I could identify with, and when I was confused it gave me a tangible community with which I could find solidarity. It still serves that function, and it is comforting to find yourself among a community who use the same label as you. Similarly, coming out as a gay man helped other people understand me better. It is deemed on some level vital to have other people understand you; were I not labelled as I am then there would be something inauthentic about how I live in the world because everyone would assume that I were something that I’m not. It’s kinda problematic that we need labels to demarcate ourselves, but I would rather use a label so as to differentiate myself that have everyone include me in a group which I don’t belong with.

I could go on talking forever about how unnecessary these labels are. To state that there is a community of gay men is to suggest that there is a coherent group of people who all exist in the same way, which doesn’t really seem to be how the world works. Labels can only ever be reductive; the label creates the group it describes, rather than describing a group which exists without the label. But the fact is that labels are one of the primary ways that we as an LGBT+ community understand ourselves and understand one another. And so I think to that end we would be unable to live without labels. It’s just necessary to acknowledge that they are not totalising, they allow for heterogeneity and we should appreciate them as fluid and flexible.

Now, the main issue I have is how people interpret these labels. So, when a gay man says, ‘if I find a girl attractive, does that mean I’m not gay anymore?’, I find it an oversimplification of how labels work. This suggests that there is somewhere a set of rules that determines whether we fit a certain label or not, and so when deciding whether a particular label is accurate we can defer to some pre-existing rules for an answer to that question. It posits an essential category of ‘gay’ that can be understood better if we keep looking hard enough. I don’t agree with that understanding of labels. Labels exist and signify as and when we use them, and to meet the ends that we desire. So, no, I don’t think fancying a girl means that you’re not gay in any inherent sense. Because being gay is something that the individual gets to decide on; there is no objective criteria to go by.

So, when re-negotiating labels as we understand our bodies and desires better I think that we only really need to consider our own needs. So: if choosing a different label instead of ‘gay’ would allow you to better understand yourself then it might mean that you are not ‘gay’ any more. But the label of ‘gay’ can be compatible with feminine romantic/sexual attraction if the person in question finds that label the most useful. If you are actively seeking a relationship with a woman then the label ‘gay’ probably won’t suit your needs and so another one might be necessary. Otherwise ‘gay’ probably works just fine.

The point is: labels are there so that we understand ourselves and so that we can manipulate how we are perceived in the world. They are inherently flawed, because the language that we have does not accurately describe things so complex as sexual attraction, gender identity, and so on. But probably the only way we have of properly understanding ourselves and others is through the medium of language, and so we have to learn to navigate these labels effectively. But it’s always down to the individual. When wondering whether a label is right, ask yourself this: does this label do what I want it to do? That’s all I think we can go off of, really.

WRB

On gender identity

I have a weird relationship with gender identity.

On the one hand, I’m very sure of my gender identity. For a long time I was confused, as I think a lot of feminine gay men are; something didn’t feel right, the label ‘man’ felt stifling but the label ‘woman’ was a daunting one, something I didn’t really understand but that always seemed within a haunting proximity. But I managed to work my way through that period of confusion. I educated myself about trans identities and realised that I do not identify completely with that narrative, and I also learnt that ‘man’ need not be as stifling as I had previously thought, it can accommodate me if I choose to accommodate it. I’ve come to accept that these labels are not absolute and can be used as and when I like; ‘man’ might be a word I’ve always grappled with, but in social contexts it tends to serve me well and I am comfortable when that label is ascribed to me. It’s less of a fact of who I am than an opinion, and I don’t experience unease when it’s placed on me. This is all a long-winded way of saying: I identify, in some loose sense of the word, as a man, and I am comfortable with that.

On the other hand, I feel like I know very little about my gender identity. I use ‘man’ because man loosely fits and it’s there, already fully-formed. It’s something of a lazy option: I wear the garment that I found in the cupboard rather than stitching my own. But when I think about myself, I rarely think of myself as a man. I don’t know what I think of myself as, but the cognitive model that ‘man’ triggers does not correspond to how I perceive myself. In other words: I’m still figuring shit out. It’s like I occupy these two ideological planes: I exist in a binary world, and I have found a secure footing there, but I also exist in a world in which gender is more elusive, and it’s in this space that I experience confusion. Ideologically I’ve deconstructed ‘man’ and ‘woman’, but in this new frontier I find myself disoriented without stable points of reference.

This reads as a contradiction – how can I be a man and not a man? But I don’t think that question is quite as counterintuitive as it seems, when I set it out as I do. Because I’m referring to two different arenas, the social and the personal. Socially I’m a man, but personally I’m not. This might seem to some an arbitrary distinction to make; perhaps I make myself vulnerable to ‘snowflake’ attacks. But all I ‘m doing is describing gender as I understand it, and as I think it is most coherently understood. Decades of gender theory has deconstructed the binary model of gender to such an extent that it’s hard to get any stable footing in this realm, and so contradictions are bound to happen for those who are exploring this new terrain. A lot of people (although perhaps not quite as many as it might seem) don’t need to distinguish between the social and the personal because the two neatly map onto each other; or, their personal gender identity is widely accepted socially. Mine isn’t. And so I’ve got a bit more work to do when it comes to understanding my gender.

For a while I’ve toyed with the labels that come with this territory: non-binary, genderqueer, gender fluid. None of those seem to fit. But I can’t work out if it’s because I don’t identify with them, or because such identities have such a stigma attached to them (in much the same way that I was scared to identify as ‘gay’ because that was the worst thing a man could be, I thought). If the terms were neutral, how would I approach them? I guess that’s inconsequential, because words (especially words related to the LGBT+ community) are not neutral. Part of adopting a label means adopting, or at least coming to terms with, its connotations. I’m not yet confident enough in my gender identity to do so. The word ‘queer’ fits, but it feels a bit like a cop-out; it doesn’t really affirm anything. It’s a useful word to free one of ‘man’ and ‘woman’, but it doesn’t really help in identifying as anything else – at least not for me, anyway. Perhaps it merely signals non-identification, and I should just accept that as where I’ll always be.

How do I proceed? I don’t know. All I can really do is experiment. I think I’ve reached this place where I’m happy to do whatever feels right. I’ve started messing about with drag and makeup and it feels good, so I’m trying not to overthink what it all means, where it situates me re: gender identity. It’s just a thing I like doing; I’ll work out the significance later on, if that’s what I choose to do. I’m not a teenager anymore, I don’t feel a pressure to be anything and I don’t have any of that adolescent self-consciousness – at least not to the same extent. I might not proclaim myself as a feminine man vocally, but I think my actions speak louder than words in this regard. I’m stitching my own garment now, and perhaps I’ll reach a day when I can take off ‘man’ and replace it with something else. Maybe I won’t; maybe it will stay in the closet. But there’ll be piece of mind when I get there. And even if I can’t pull it all together into a single garment, that’s fine. The process of trying to work out gender is perhaps the only place where gender exists.

Identity is a fucking minefield. Every day there seems to be newspaper stories about identities that seek to move beyond cisgender binarism, and I think they seriously misunderstand how identity functions. Gender can’t be fitted into a headline, into a short phrase. And if that’s how gender operates for some people, good for them. But failing to meet that standard isn’t failing. I see things like ‘my gender changes on a daily basis’; and this is true, I feel it, but when it’s condensed into a six-word phrase some of its essence is lost, and it’s easy to ridicule. And that’s why it’s so hard to push non-binary identities into the social realm. They are so personal, I think, and I’d be hard-pressed trying to convert that into something that anyone else might understand. I appreciate the efforts of those who try and do this, but until I am more sure of myself I’m not sure I can partake in it.

But I think what I can do is open up this space of confusion. Because that’s what I think gender is: it doesn’t make sense, but it doesn’t have to. I’ve kind of been forced to probe my gender identity because something’s not quite right, but I imagine that if a lot of people similarly probed their gender identity it would not hold up as stable. Those who push at the boundaries of gender, I think, are those who come closer to understanding it. Not to make myself superior to anyone else; all I’m saying is that these kinds of monolithic concepts need to be interrogated. The act of interrogation is, I think, where gender is its most potent. I feel gender most when I push it. When I wear heels I don’t really feel like a woman, but I feel gender to a greater intensity than at other times. And sometimes I don’t; sometimes I put on the heels and it doesn’t connect, I don’t feel much at all. I think it’s perhaps more useful, for me at least, to note when I feel gender the strongest, rather than trying to calibrate these feelings on a scale from ‘man’ to ‘woman’. All of this is a bit vague, and maybe I’ll take it all back later, but for now it makes a bit of sense. Perhaps I’ll leave it at that.

Also: it’s refreshing to write about gender identity in this way. I’ve not told many people that I like wearing heels and makeup.

WRB

Sam Smith & Being Non-binary

In a recent interview with Jameela Jamil as part of her Instagram ‘I Weigh’ series, Sam Smith spoke about how he struggled with his gender identity from a young age and has increasingly identified with the labels genderqueer and non-binary, the latter being the term he explicitly used to define himself. A few other celebrities – namely Miley Cyrus and Ezra Miller – have come out as genderqueer and non-binary recently, and such stories always stimulate discussions about gender, often banal but still necessary to have. I thought I’d share some of my thoughts about this topic.

To begin with, I felt incredibly liberated by the interview. I identified with a lot of what Sam was saying: feeling somehow ‘behind’ and isolated within the gay community, of feeling confused from a young age for not fitting in with ‘the boys’ but never being one of ‘the girls’. I was shocked but impressed upon hearing that prior to becoming famous he for a period of time stopped wearing men’s clothing, and his discussions of the intersections between gender identity and fame were insightful. It’s also just great to see someone within the public eye admitting to being confused about body image and gender identity. As someone who has been very confused about gender it’s validating to see these discussions being had in a respectful space.

Now, a few issues I had with what Sam had to say. I thought some of his language was… problematic. He states that he has previously considered having a ‘sex change’, and I find this language a bit outdated, implying that transitioning is the result of having one operation rather than being a process that involves so much more than merely surgery (not to suggest that Sam means this with what he says, but I think that such terminology connotes this old-fashioned approach to the transgender experience). I think he could benefit from saying something like, ‘I debated whether I might want to transition…’ as this is, I think, a better way to discuss gender identity.

Similarly, he also claims that he at times ‘thinks like a woman’, which begs the question: what exactly does it mean to think like a woman? It seems to confirm the binary that he later goes on to deconstruct through coming out as non-binary, seems to presuppose the pseudoscientific notion that men and women think in fundamentally different ways which I am reluctant to accept. Again, I think this is a linguistic nuance and does not necessarily mean that Sam believes in what his language implies. It also probably comes from the fact that he came out in an interview rather than in a thought-out statement, and sometimes language can be awkward when spoken compared to when planned and written. I would like to quiz Sam on what he means by ‘thinking like a woman’, and hopefully dispel the gender essentialism such a claim suggests. But I also think this is a result of his confusion, his lack of exposure to the trans community. It can take a bit of adjustment to become accustomed to how gender ought to be spoken about because much of the language used in mainstream society to describe gender comes from a time before it was understood as it is now. I don’t think Sam should be punished for not being an expert on gender; I think it’s incredibly brave for someone subject to so much scrutiny to speak up on an issue which is so contentious. It’s perhaps enough to say, ‘x is a bit problematic for this reason, so maybe use y instead’. Anything more overtly critical might discourage conversation, which I don’t think benefits anyone. No one should be afraid to speak, but at the same time no one should be unwilling to learn when they misspeak.

Now, onto some of the criticisms that Sam has faced following his coming out. I’ve seen claims that coming out as non-binary enforces the gender binary it seeks to transcend; since gender is so fluid nowadays, to place a third category between binary oppositions makes the oppositions more legitimate, seems to confirm that they are essential categories (as is non-binary) rather than social constructions.

I think this criticism has some credibility. Rather than deconstructing the binary, creating a non-binary identity could arguably introduce a third term, and so does not move beyond it but merely reconfigures it to a system of 3 rather than 2. As such it doesn’t really signify much of a movement beyond traditional notions of gender; sexism could still exist, and it still posits a stable gender marker and so is subject to the same scrutiny as ‘man’ and ‘woman’. In an ideological framework, I think this is true. There is no such thing as gender, I believe, beyond things which signify it. In an ideal world there would be no gender, it would be recognised as an ideological fallacy and so coming out as non-binary seems counterintuitive under such a model of gender. Under this view, though, coming out as anything should be criticised; being trans confirms the gender binary, being gay supposes that there are such things as genders to which one may be attracted. I think to only direct this criticism towards those who come out as non-binary would not really be fair.

Furthermore, while it is generally accepted that gender is a social construct, that does not mean it is insignificant. Ideologically, yes, gender has no inherent meaning, but in the world as we understand and live in it there are coherent understandings of gender, there are such things as men and women and such categories have material consequences. Under this criticism, anyone who identifies as a man or as a woman should be criticised, which would be the majority of the population. To claim that non-binary identities enforce a binary which does not exist overlooks the fact that in society the binary does exist, and however problematic this might be we cannot overlook the conditions of the societies we live in. To claim a non-binary identity is to say that in society there are such things as men and women, and living in that society I do not identify with either of those labels. To deny non-binary as a legitimate identity would leave only two options, man and woman; once more we return to the binary. And coming out is a powerful thing; the identity is created in the act of coming out. If no one came out as non-binary, even if such identities existed, then there would only be the identities of ‘man’ and ‘woman’ visible and accessible. I find it incredibly powerful to come out as non-binary, because it is always done in the context of a society in which the gender binary is oppressively in operation. I think it deserves applause, not immediate criticism.

Another criticism I heard was that Sam was coming out as a publicity stunt. This is viable; gender is a hot topic at the minute, and is bound to catch a few headlines. I don’t think there’s much to say about this, other than that I don’t personally believe Sam has much to gain in coming out as non-binary. He is pretty much at the top of his game. I know this is not the best way to judge, but I thought he came across as incredibly real and honest in his interview, and so I would like to think that he’s not taking the piss. To say that he is appropriating an identity for the sake of publicity excludes him from the community, forces him into an identity he claims not to identify with, which seems anathema to what the queer community is all about. I think all we can really do is accept people’s proclamations about their own identity, and hope that no one would take advantage of this for personal gain. Maybe this is naive, but otherwise we end up policing identities and who has the right to be in the community, which is a worse evil, in my opinion.

I think there are more things to be discussed, but I’m starting to ramble now, I sense, so I’m going to leave it there.

WRB

On Pseudonyms

I don’t know if this matters much, but I write this blog under a pseudonym. I do this for a number of reasons. On more of a practical level it affords a certain amount of privacy, it makes me as an individual less vulnerable to criticism; WRB is something of a shield I can hide behind. It’s not that I’m writing as anyone other than myself, but I want to distinguish myself as a person from myself as a writer – I can’t necessarily take responses to WRB IRL because the domains of a blog on the internet and conversation between two individuals are completely different, and I can’t have the same kinds of discussions across them, I don’t think. It’s a way of containing discourse, and it means that what I write doesn’t taint who I am and who I am doesn’t taint what I write. For me it’s the best way of maintaining a secure sense of who I am. I always found it difficult setting up online profiles, responding to emails etc. because it felt like I was projecting a self somewhere it didn’t belong, and I was always worried that the self I projected to one domain wouldn’t match up with the self of another domain. Using a pseudonym allows me to avoid this difficulty because I am not claiming any kind of continuity between me and WRB (I do, as a matter of fact, think there are many continuities, but I’m not claiming them as given, meaning I don’t have to account for any differences). It might be an arbitrary distinction to make, but its one that I stand firmly behind.

I’ve always been intrigued, perhaps tormented, by the idea of a ‘self’. I’ve never been particularly sure of what kind of self I am. When I was younger and started creating profiles on Facebook, Twitter, etc. I initially found it liberating, because I could create whoever I wanted and that was me and it was great, I was free where I’d always felt oppressed as a living person. But then I’d get carried away, and the person I’d project into these internet spaces would run away with itself and I’d find this massive distance between me and them. And then curious things would start to happen; people IRL would talk about things internet-me had done, and I’d find myself unable to respond because of this gap that had formed between them. I was always flabbergasted that people could be the same person online and IRL! That was something I never mastered, even to this day.

I think social media is great, but personally I was always troubled by the idea of having an online profile. I think there is an assumed identical correspondence between IRL self and profile self, but I was always confused because to me the differences between them were glaringly obvious. And I think mysterious things happen with the creation of an online self. It seems obvious that there is an original ‘me’ who exists in the world and the online self is a simulacrum / representation of that, but I found that increasingly the online self was starting to constitute the ‘original’ self; it seems the ontology had got mixed up somehow.

I feel like that was full of postmodern jargon, so I’ll use an example to let me fully understand what I’m trying to say. When I was about 13 I started using the internet heavily, excessively I think, and I started to find myself there. I identified myself as gay, found this new world I could relate to, and I became a fucking massive Lady Gaga fan. I created this online self who had at least a hazy understanding of who he was. But IRL I was a nothing; I’d spend hours and hours reading about Lady Gaga online, but if someone talked to me IRL about her I’d have nothing to say, there would just be a blank and the conversation would move on. I was curating an online persona at the expense of an IRL persona. For a long time it felt like the only self I had was the online one, which was distressing because to get by in the world I needed a firm sense of self and I didn’t have one. I still struggle with this to this day I think, but I’m definitely getting better. I decided that I needed to hone who I was as a living self because I couldn’t keep up with the online self I’d created. Herein lies, I think, one of the inherent dangers of the internet; it encourages the creation of a particular kind of self that leaves the one IRL sadly lacking.

This is not to say I think that the IRL self is better or more primary than the online self; I think they are expressions of identity in two different metaphysical spaces, and neither takes precedence. I do, however, think that a balance needs to be struck between these two things. Selves are utilities in that they allow us to do things in the world, but if one of those selves is not doing its job then there’s a problem. For me, having a solid sense of self online is pointless if there is no equal counterpart IRL. Maybe I’m being old-fashioned; perhaps the world is heading towards a place where the internet is a more primary space than IRL, and so it’s a waste of time to try and hone a self IRL. But the point, if I can try and remember how I got to talking about this, is that to call two things the same name when they are so vastly different is inherently confusing, and for me it created many difficulties both psychological and material. For me, the movement beyond this started by deleting my Twitter account and creating an anonymous Instagram profile (I like Instagram, and wanted to partake in it without facing the turmoil of online self-curation). I keep Facebook posts to a minimum, and am wary of when the self I am creating differs too much from me.

Back to pseudonyms. I’ve always been obsessed with pseudonyms. Some of my favourite people use pseudonyms: writers, musicians, drag queens, porn stars. I’m interested in pseudonyms because of what exactly it is that they create. Some drag queens report a complete character change when in drag, others an enhancement of character, some no difference at all. I know that it’s more than just a name which creates this difference, but I think to name a thing that one does with one’s body differently to the normal use of the body constitutes a splitting of the self and so increases this sense of a personality split. I’m drawn to pseudonyms because I think the self is inherently fragmented, we becomes new selves as we do different things with our bodies, and so there’s perhaps something more honest in using a different name. Why not? There’s the Jekyll-and-Hyde appeal as well: I can don the mask of WRB, commit whatever debaucheries I would like on this blog, and then take off the mask and no one can pin it to me, the person who sits and types and goes about the world. I’m being emphatic here; I think I’m being honest in what I write; these are thoughts I’ve had in my head throughout the day. But I think it generates interesting questions. What, exactly, is WRB? Even as I tell you that WRB is not a person in the sense that you might envision it, I think it’s incredibly difficult to not think that there is a person named WRB who sits down and writes. The use of the different name makes it impossible not to consider the relationship between writer qua writer and writer qua person. The equivalency we are compelled to make might not be all that simple.

I’ve also noticed some things about the use of the pseudonym. It’s easier to make claims about myself. All of those things I wrote about myself on my introductory post are true facts about me, but it was easier to state them when they were not being attached to me. Maybe this reveals something about my own lack of confidence, but I think it’s interesting nonetheless. Maybe if I can successfully create this online persona then I will have more confidence to be that person IRL; not in the way I did when I was a teenager, but in a genuinely worthwhile and useful way. I can strengthen WRB‘s voice, and since that voice is not all that different from my own I can appropriate it to embolden my own voice. I don’t know if that will happen. We’ll see. I would like to have a professional writing career and this is the name I would write under, so at some point I am expecting to have to unite WRB with myself. That will be an interesting moment. I think this self-awareness of what I am doing will afford me prudence which will mean I won’t get carried away and face the crisis of self I’ve encountered so many times before. Fingers crossed. Who fucking knows what might become of WRB.

WRB

Literary Crushes

Today I listened to minisode 2 of the podcast Literary Friction and Octavia and Carrie’s discussion was about literary characters they have a crush on. The basis of their debate was that one of them (I can’t remember which, Carrie I think) had to dig really deep to find a literary character she had a crush on, whereas the other could list them indefinitely. I thought it was an interesting discussion; they related it to styles of reading, with the former discussing how there is a critical pane of glass between herself and the literary world she reads about and she finds it difficult to visualise fictional worlds, whereas the latter reads visually and is very much ‘within’ the text. I thought I’d come in and share where I stand on the matter.

I’m personally a reader who very rarely crushes on literary characters. In fact, I struggle to think of a single character I have a crush on. I think it’s important to define exactly what a ‘crush’ is here, because I think there’s a risk of equivocation if it’s not pinned down. I think ‘crush’ operates on two levels: it is romantic and sexual. Although they touched sometimes on the sexual, I think Octavia and Carrie were mainly discussing crushes in terms of romantic attraction, or they were in some way assuming a link between the two.

This distinction is an important one to make, I think, especially in terms of my own identity. I feel romantic attraction very rarely – I can probably name on one hand the number of people IRL that I’ve had a crush on – whereas I feel sexual attraction all of the time. So when I probe to think about literary crushes it is not really a surprise that I struggle to come up with anything, because how I think of ‘crush’ is closely linked to the romantic and the sexual, and since IRL I don’t feel strong romantic attraction it follows that the same would be true of literature. But then I got to thinking about different media, and I realised that I do tend to crush on men in more visual media quite a lot. For example, I think it’s fair to say I have a crush on Bradley Cooper’s character in A Star Is Born, and I do have crushes on celebrities quite a lot (I think celebrities are a certain kind of fictional character, but that’s a discussion for another day). And so I think it must be something to do with the literary text in particular – rather than fictional worlds in general – that makes it difficult for me to connect to.

Let’s unpack this a bit further. I think it must be something about the lacking visual element of the literary text that leaves me indifferent to the characters, because I don’t read in a very visual way. Let’s take Jackson Maine from A Star Is Born as an example. I find him physically attractive, not just aesthetically but in the way he moves, the small inflections of his character, as well in his emotional vulnerability. There are certain crucial aspects of this which are missing from the literary text as I experience it while reading. I think I erect a critical screen between myself and a text and I think of characters in the abstract rather than as real people, unlike in a film where I do consider the characters real people. It’s strange how a visual element can change how I relate to characters – it would be interesting to read a literary version of A Star Is Born and see whether my opinion on Jackson is different. For myself attraction is a very physical thing and so I suppose it makes sense that I would be more attracted to characters in film than fiction; I find it hard to have a crush on something I consider abstract.

At the same time, I find some texts to be very sexually stimulating. I think that desire can be a linguistic phenomenon as much as anything else. I read Hollinghust’s The Swimming-pool Library at the start of 2019 and I found it to be a very arousing text which was successful in its depiction of gay male sexuality (even if some of its encounters were problematic – I’ll probably touch on this in another post). I was very turned on when I was reading the novel, something which I don’t think I’d much experienced before and I found reading the text quite liberating. It gave me a new understanding of pornography, which I had only understood as visual; I’d never thought that I could be much stimulated by text. But having said this, it would be wrong to say that I had a crush on Will or on any of the characters in The Swimming-pool Library. I might have found the actions they performed sexually arousing, but who was performing them was irrelevant. The sexuality they expressed was what attracted me. Perhaps a crush, at least for me, requires a strange combination of physical and emotional attraction, and although literature can capture elements of both it fails to cohere them in a single character, and so pales to film in this regard. (Not that I prefer film, mind; literature is definitely my preferred medium. But I don’t read books to find crushes, so it’s not a massive failing for me.) I’m not saying that I’ll never fancy a literary character, but it doesn’t really seem likely with what I’ve read before.

Another idea to throw out there: maybe it’s to do with sexuality. A lot of the books I’ve read have been in an educational/academic context, and so they have tended to focus on heterosexual romantic encounters. Maybe my inability to crush on literary characters comes from the fact that I’ve been reading heterosexual relationships, and since I don’t see myself in them it follows that I wouldn’t share in their articulations of desire. I’ve not read that much fiction about gay men and so perhaps that’s where my crushes are. But Jackson Maine isn’t queer, so maybe sexuality has nothing to do with whether I fancy someone or not. In the podcast they mentioned that literary crushes can transcend gender and sexuality, so maybe literature is a space where it is about feeling rather than the identities of those involved. As an unromantic person I may be excluded from this system altogether.

I think it’s interesting to think about the relationship between sexuality IRL and in fiction, because I think fiction opens up a kind of fantasy space where you can fancy whoever you want. It operates like porn in that regard. I think there’s a very special relationship between literature and porn, and literary representations of porn are certainly something I’d like to study further. Both in some way seem to dictate the kinds of sexuality that we are capable of feeling.

WRB

Get Out

This is a weird one to start with, because 1) literature is the medium that I’m the most familiar with, not film, and 2) issues of race are something I’m always wary about discussing. But I figure it’s always better to talk about an issue, providing it comes from a place of respect, than to shut down all discussion because errors might be made.

First, some general comments about the film: I really enjoyed it. The aesthetic of the film is really strong in terms of camera shots, the weird motifs (the deer, the tea cup) which recur throughout, and the portrayal of middle-class whiteness in the Armitage household was done really well, in my opinion. I thought it was aware of itself as commenting on an important issue, but it wasn’t overdone so as to make it inaccessible to a white audience; but neither did it seem to titillate a white audience too much. I found it didn’t last too long, it wasn’t overcomplicated, but the somewhat simple plot was very powerful and so it didn’t lose anything because of this. (You can probably tell that I’m not accustomed to commenting on films. Hopefully I’ll get better in the future.)

Now, the big issue: blackness. I’m white, and that makes it difficult to talk about being black. What I think the film showed really well was the frustrations that occur when black and white people interact; it showed that although different races ought to interact, not all interaction is good when it comes from a place of ignorance, and not all attempts from white people at including black people are noble in their own right. Example: all white people mentioning a black celebrity (usually Barack Obama) that they like, as if to prove that they are racially enlightened. Obviously I can’t know exactly what this is like, but I think my position as a queer person makes it possible for me to understand this frustration. I think the point is that when you occupy a position taken as universal (i.e. white), everyone is able to discuss that culture because it is accessible to everyone, in comparison to occupying a marginal position in which people who claim to understand the culture do so on a very superficial level, so you end up discussing the same handful of topics again and again.

What is to be learned from this? I’m thinking about whether it tries to be didactic. Is it trying to teach white people how to interact with black people? I think that would be doing the film an injustice. I think it was more a tongue-in-cheek recognition of these frustrations of attempts at interaction; white people seek to show how socially conscious they are by engaging with black people, but in doing so reveal how out-of-touch they are with the experiences of black people. White people and black people cannot relate to one another on the basis of race, so it is not necessary to do so.

I’m noticing myself kind of struggling to express myself here, and I think it raises important issues about white people talking about race. I don’t consider myself ignorant, but I’m encountering this difficulty in articulating myself because the issue is such a contentious one. But I think it’s important to talk about this stuff. I was in a tutorial today on Americanah, and the class is such that the majority are white, and there was not very much productive discussion of race. How, as white people, are we supposed to approach these issues? I think the first step is to take a back seat. All I can really do is use the voices of others because it is not a voice I have myself. Part of me wants to try to find ways in which I can relate my own experiences of oppression to oppression due to race, and I think that can be a useful way to conceptualise what it is like to experience racial discrimination, but it is also necessary to acknowledge the ways in which each ‘category’ of oppression operates differently, in different locations and in different ways. It’s somewhat reductive to try and relate everything to one’s own experience, but I think it is kind of required because as human beings we are limited to our own experience and this is how we view the world. I don’t think there’s much productive to be said for a white man discussing race; I’m not bringing anything new to the discussion, and no one is going to take me as an authority. But to exclude white people from discussions of race is not useful either, because black and white people are always going to interact with one another, and discussion of contentious issues is important. Adichie has spoken of the western world’s obsession with comfort; we feel discomfort when approaching contentious issues, and so refrain from getting nearer to them. Maybe it’s better to say something harmlessly useless than to say nothing at all. I don’t know. It’s difficult.

Back to the film: the other main thing that I found interesting was its metaphor of hypnotising and brainwashing. I think it literalised the idea of how subject positions are conditioned by ideology, how people are made to think and behave in certain ways by institutions of power. So the powerful whites are able to brainwash the powerless blacks into adopting a white consciousness. As fiction it was extreme, but I found it an extension of how this can be a reality in the real world. It’s image of white supremacy was horrifying but not too much of a stretch. I’m not sure how useful the ending was: it seemed to position white and black people in positions of violent tension, and didn’t seem to offer a way out of this. But perhaps it’s worth remembering that Chris was not fighting all white people but rather white supremacy, and his triumph was over that, which perhaps makes the ending make sense. And it is as much the job of white people to eliminate white supremacy. It is easy to watch the film as a white person and feel like, I’m not one of those white people, it isn’t speaking to me. But I think all of us are to some extent those white people; it’s not a extreme state, there are shades of white supremacy. Perhaps it’s about recognising the problematic supremacist parts of the self that stem from being white.

I’ve likely missed a lot of important things from the film – there are no doubt interesting discussions to be had about its relationship with cloning, for example. But these are the thoughts that I had.

WRB

Hello

I thought I would start with a little introduction to myself.

I’m a 22-year-old, gay, queer, male, student originally from Yorkshire but currently completing my undergraduate degree in English Literature in Scotland.

I felt the need to start this blog for a number of reasons. The major catalyst for doing so was reading Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, and I was inspired by Ifemelu’s blogging as a mode of writing free from the traditional constraints that I’ve become accustomed to in academia; although I enjoy academic writing it can be a bit stifling to condense all of your ideas into the essay form, and I was seeking something which would allow me more creative freedom. I mean ‘creative freedom’ in the sense, not of fiction per se, but more in terms of the requirement that I express myself in a very well-structured, coherent, well-supported argument. I think these things are absolutely necessary, but I sort of found myself trapped within this narrow idea of what successful thought looks like. I suppose this is a way for me to just muse on what’s happening within my head, without feeling the pressure of needing to use the best words in the best order to make the best claim. It’s a way of admitting to myself that there is value and validity in thoughts that come off the top of my head and that I haven’t necessarily articulated into anything greater than just a few strands of thinking that I find of interest. I think all of this is to say: I wanted the freedom to write, to sit down and just say things and not place them in any context beyond themselves.

So, a few goals for this blog. It’s largely up in the air at this point. It’s more of a repository for the process of thinking than anything else. I don’t want to edit myself much, if at all, I just want to sit down and type and see whereabouts I end up. There’s not anything in particular that I want to write about, other than the things that enter my head at any particular time. This seems broad, but being as I am I find myself thinking about certain things more frequently than others: living as a gay man, identity, academia, to name a few. (I same to name a few because my mind has inevitably gone blank of all the things it usually thinks about.) I also want to write responses to the books I read, because I’m so used to thinking about books critically and in relation to canonical debates that I’ve sort of lost my ability to say whether or not I like books, what they mean to me, and why. Being a critic you’re encouraged to write from a stance of rationality and reason, which makes it easy to lose the sense of books as personal items that we respond to emotionally. I’m sure I will not easily shake off the academic training I’ve become accustomed to, but I want to try and create a new voice for myself that isn’t quite so rigid and inflexible.

That’s all there is to it, really. I can’t promise any kind of consistency, guarantee any quality control. All I can really say is that when I have a thought I will try and come here and give it a form that can rid it from me and hopefully stimulate some intellectual response in you. I don’t want to be so presumptuous as to imagine a massive audience here, to suppose that anyone cares what I’ve got to say, but it’s a bit demoralising to suppose I’m speaking to an empty room so for the sake of my sanity and morale I’ll assume that someone gives a fuck.

That’s all there is to it, really. Here goes.

WRB